Well-being

A fundamental goal of sustainability science is to maintain or increase today’s as well as future human well-being. This goes well beyond current economic welfare measures, even those that add social and environmental values to the traditional GDP main development index. Well-being is a concept that includes many more aspects than have traditionally been used.

For example, the Gallup institute uses measures of physical, social, financial, career and community.

National accounts of wellbeing is an effort by University of Cambridge and New Economics Foundation in the UK compiled accounts of wellbeing for 22 European countries. Data on subjective well-being were collected in a major 2006/2007 European cross-national survey through a detailed module of 47 questions, estimating: emotional well-being; life satisfaction (“happiness”); vitality; self-esteem and resilience; positive functioning (including freedom and meaning); positive relationships; and trust and belonging. Denmark came out as the country of the highest well-being and the other Nordic countries were all in the top, whereas the former communist countries were at the bottom Link.

Research on happiness regard human wellbeing as the ultimate objective. Subjective information, such as the initiative by Cambridge University above, is usually combined with objective data on life expectancy, education, income distribution, etc. The inclusive wealth index (IWI) by UNEP is an attempt to create an inclusive wealth index that relies on indexes that are objectively measured by available data. It supplements GDP with indicators of the economically most important natural capital, such as forests, fisheries, agricultural land, fossil fuels and minerals. Countries exhausting their natural capital may increase their GDP but are “punished” by the IWI. The index measures an asset’s wider value to society, and not only the price for which it could be bought or sold.

However, IWI does not include biodiversity or regulating ecosystem services because these are hard to quantify. The IWI hence focuses on the economic aspects of sustainability (GDP adjusted by some natural resources) whereas research on well-being focuses on social aspects. It seems to be more difficult to agree on, and measure, what issues of environmental sustainability one should include.

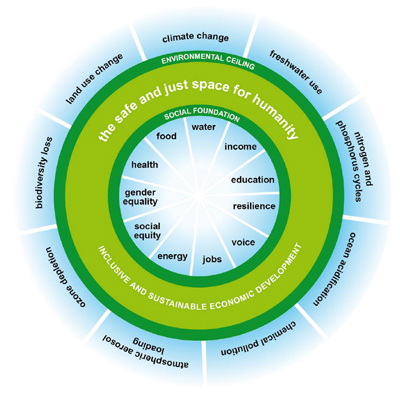

The Planetary Boundaries concept (that you have been introduced to already in previous modules) attempts to establish a framework to determine the safe operating space for human development. The planetary boundaries are biophysical limits that are non-negotiable. Kate Raworth combined the planetary boundaries with their social foundations in a recently proposed framework, aptly named “doughnut economy.” This suggests that a safe and just space resides within two circles of limiting planetary boundaries and meeting necessary social foundations.

The eleven social foundations in doughnut economy are also similar to the variables emphasised in a recent report called the Stiglitz commission:

”To define what well-being means, a multidimensional definition has to be used. Based on academic research and a number of concrete initiatives developed around the world, the Commission has identified the following key dimensions that should be taken into account when defining what well-being means. At least in principle, these dimensions should be considered simultaneously:

- Material living standards (income, consumption and wealth);

- Health;

- Education;

- Personal activities including work

- Political voice and governance

- Social connections and relationships;

- Environment (present and future conditions);

- Insecurity, of an economic as well as a physical nature. “

How to measure Well-being?

While a consensus understanding is emerging that sustainability based on well-being is a multidimensional effort that requires both social, environmental and economic aspects, the details of what and how to include different aspects into the concept is still an ongoing debate. However, even if a consensus understanding could be reached on what indicators should be included, a major obstacle would be how to measure these.

If sustained human well-being is accepted to be the ultimate normative goal, then the eight dimensions emphasized by the Stiglitz Commission are instrumental to this goal. Some of these goals may also hold intrinsic value, e.g. health and political voice (freedom & democracy). The natural environment has a fundamental value because it provides life-supporting services to people and some loss of it may have negative and irreversible effects on human well-being. Material living standard is important but can be seen as included in social objectives of security, freedom, health, etc. Furthermore, an economic recession is not irreversible although it may decrease the options for well-being such as health, jobs, etc. Economic growth is often regarded as the main instrument to achieve social goals and we should not confuse the means (instruments) with the goals.

As mentioned before, sustainable development is about sustaining human well-being and this requires safeguarding sustained services from the environment. The economic dimension of sustainable development is about securing the social and ecological systems (social and natural capital) which in turn are needed to sustain economic activities. Thus, it makes little sense to equate economic sustainability with economic growth, especially if GDP is growing at the expense of social or ecological sustainability. There is a general agreement among economists that economic growth is not a good indicator of well-being, but at the same time, there is a general agreement among politicians that economic growth is important to provide the means for various political goals.

Subjective well-being is measured by questionnaires, like the National Accounts of Wellbeing, discussed above. Many components of well-being are not easily quantifiable from existing and objective data. Freedom, happiness or resilience are a few examples. Although the issues to include and the exact formulations are supported by rigorous psychological and sociological research, there is something hypothetical about questionnaires; they do not reveal the actual choices by people, only stated preferences (Kiron 1997). Objective social data can be gathered through income, income distribution, health (sick-days or life expectancy), education (proportion of population with a secondary education, results in school tests, money spent on education), etc. However, although these are objective data it can be questioned to what extent they really reflect well-being.

Measuring wellbeing by a set of indicators therefore seems to be a very complex task. This can be illustrated by the EU which has identified over 100 sustainability indicators to measure changes in sustainability within ten dimensions. Twelve of these indicators have been chosen as head indicators (the dimension “Climate change and Energy” got three of these twelve).

You will probably object to some of these head indicators and ask why other indicators are not emphasized. But this is unavoidable since the whole idea of well-being, just like to standard economic definition of utility or welfare, is essentially subjective.

References

Kiron, D. (1997), ‘Economics and the Good: Individuals – An Overview Essay’, in F. Ackerman

- Different organizations come up with different sets for inclusion into the concept of human well-being. Why do they differ so much?

- Is a consensus desirable or will this concept benefit from continuous diverse approaches and interpretations?

Contributors

Jon Norberg, Thomas Hahn

Leave a Comment