Defining Sustainability

Sustainability is a very broad concept as shown in the goals it attempts to solve. To implement sustainability in policies, our concepts and goals need to be more operational and specific. Making a general concept more specific will undoubtedly also make it easier to disagree on the definition. This process is crucial in science, as knowing WHAT to disagree on is fundamental in discovering new understanding or perspectives. Thus, as we begin to make sustainability more specific using different approaches from different disciplines, we are also able to highlight and hopefully resolve important controversies. Sustainability is, however, not definable as a positive statement, since there can be as many indices of sustainability as there are normative definitions of what we want to sustain. The concept itself thus becomes a democratic and highly diverse concept defined over scales of global, national and local communities.

Human centred

Humans are the dominating force on the planet. No ecosystem is pristine anymore in the sense that it is not affected by human activities. The conservation paradigm of many decades ago to preserve nature from humans is far gone. We need nature and nature is shaped by us. However, since we can establish that human well-being is intrinsically linked to healthy ecosystems, the goal of sustaining human well-being over time is also a quest to maintain ecosystem functioning and goods and services they provide for society. By incorporating these goods and services in human well-being we can begin to define the goal of sustainability. Note, however, that this view of linked social-ecological systems is only recently becoming more recognized, as you will hear in the TED talk below by Kate Raworth.

Sustainable human well-being

Let us for now assume that we have a measure of well-being for humanity, or of people in one particular region and let’s call that W. For now, we will assume that we got it right so that W actually captures everything that contributes to human well-being. Let’s also assume that W depends on many things (as we discussed in the previous section), but let’s begin by grouping this into financial (F), human (H), natural (N), social (S) or physical (P) capital such that we can define well-being as W(F,H,N,S,P). With this sweeping simplification Ken Arrow and colleagues argue that to calculate intergenerational well-being, i.e. from now and into the future, we just sum the well-being over time and add a discounting rate (d) so that well-being in the near future is valued higher than well-being in the more distant future.

We will discuss discount rates in the next section, but for very low d, we would value the future almost as much as today. With high values of d, we won’t care so much to receive any benefits in the future.

Arrow and colleagues now make a simple but powerful statement. Sustainability is , or in words: the rate of change of integrated future well-being must never be negative.

There, a mathematically precise definition of sustainability….or rather, we have defined general criteria for knowing when you have it. W(F,H,N,S,P) represents the flow of utility from your capital stocks at any point in time. We are, however, left with the quite complicated task of actually defining W(F,H,N,S,P), as well as how the capital stocks work and relate to each other. We have already hinted at the issue of what extent different capital types are substitutable. How much can we continue degrading natural capital to enhance other types of capital and claim this will benefit the wellbeing of future generations? According to the ‘strong’ definition of sustainable development, the stock of natural capital must not be reduced over time. The argument is that the goods and services from natural capital can only to a small extent be replaced by other forms of capital. The ‘weak’ definition of sustainable development is that the sum of all capital stocks should not be reduced. This allows for substitution between the capital types. The argument is that as long as we avoid thresholds, we can continue degrading natural capital if the negative human well-being effect is more than compensated for by increasing other types of capital. This is what we have done all throughout our history and surely our well-being today is higher than hundred years ago. But will it continue to be so? Have we already passed some irreversible threshold setting future well-being on a declining trajectory?

In the next section, valuing the future will talk more about the use of discounting rates to estimate the potential value of goods and services in the future.

Interlinked capital stock management

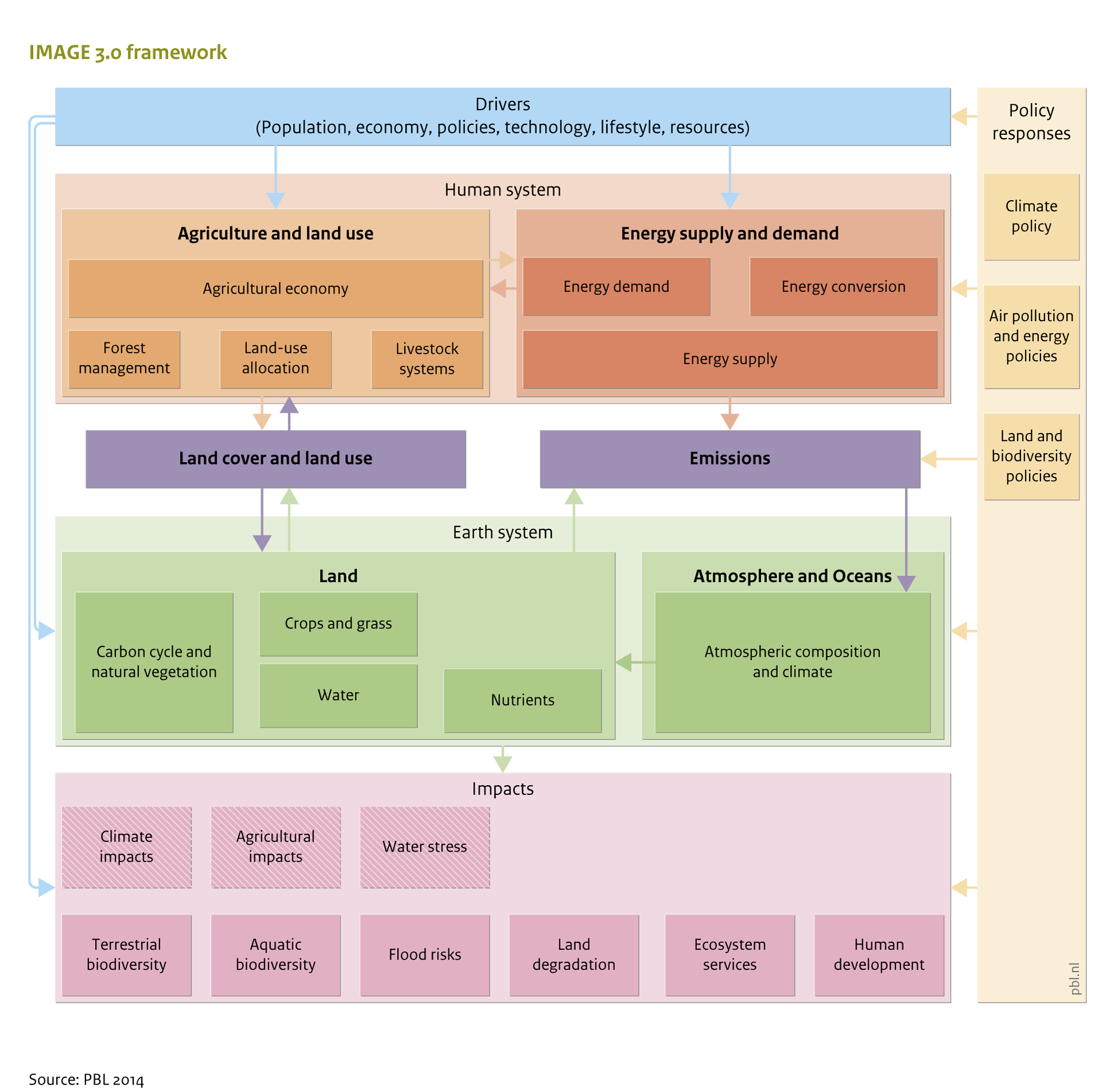

Up until now defining sustainability doesn’t look all that complicated, but we have left out some of the details until now. When we defined intergenerational well-being above it looked very static. In reality, human actions change the flow from capital stocks, some intentionally, some unintentionally and some through interdependency between capital stocks. For example, to ensure efficient human capital, people need to be healthy and productive. However, if you take production capital into consideration, such as machines, energy or information, production may produce pollutants, and as a side effect reduce human capital through reducing life expectancy or increasing extended sick leaves. Thus, in reality,the production units of the different capital types form an entangled and sometimes very complex web of interactions. Unraveling this web, piece by piece, through scientific studies of important linkages is an ongoing research field. Notable efforts include the DICE and RICE models, the PAGE model used in the Stern review PAGE, as well as IMAGE. These models attempt to include some of the main complexities that have been highlighted as crucial (see IMAGE flow chart below), but they are still extremely simplified (DICE/PAGE more so than IMAGE).

Most indexes of human well-being mix economic, social and environmental variables and are thus a weak measures of sustainability. Ideally, “a sustainability index should be derived from a physical-economic model predicting future interactions between the economy and the environment in a reliable way, to send us correct forewarnings of non-sustainability” (Stiglitz).

Human needs require resources

As you will hear in the talk by Kate Raworth below, human needs and well-being require resources, and using these resources affects the planet’s support system. Understanding the concept of sustainability described above, and the complexities of interrelations among production units of this well-being, is important for policy-making. While some attempts are made at integrated models as mentioned above, the scientific community is working on many of these relationships with a narrower focus. For example, the role of water for producing food but also for regulating the climate; or the impact of land use change on biodiversity but also on the importance of biodiversity to enhance production, such as through pollinated crops or multiple ecosystem services in forestry. Thus, from many lines of research, important conclusions are communicated to policymakers which may add up to enough evidence to implement changes. Biodiversity is such an example, which, although being an extremely complex issue, has gained enough support to make its value heard in global governance, which has resulted in several major treaties that concern biodiversity conservation, for example the UN Convention on Biodiversity. Thus, while we may lack a completely integrated picture, the adaptive multi-level nature of governance and the continuous dialog between science, policymakers, NGO’s and the public, is working towards a new understanding of human development from the bottom up. But as Kate Raworth tells us in the talk below, the main language that drives global human activity today is economics and it is thus of paramount importance that the crucial insights of planetary boundaries and linked social-ecological systems are acknowledged in economic theory and applications.

Inclusive economics

- What is your own definition of sustainability. Does it match with any of the definitions presented above? If it is different, why do you think that is so?

- Can you explain the difference between sustainability and well-being?

Contributors: Jon Norberg, Thomas Hahn

Leave a Comment