Agreing on the goal of sustainability

Ever since the Brundtland report, Sustainability has been a global issue.

The report deals with sustainable development and the change of politics needed for achieving it. The definition of this term in the report (“Our common future”) is quite well known and often cited:

“Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.

It contains two key main concepts:

- The concept of needs, in particular the essential needs of the world’s poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and

- The idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment’s ability to meet present and future needs.

Furthermore, the Brundtland report made one crucial point that has in modern approaches to sustainability been even further emphasized: The sustainable use of economic, social and natural capital are inseparable. While many approaches to achieving the merging of these “spheres” are being developed in science, governments and non-governmental organizations, we will focus here on the approach used by many contemporary leading sustainability research centres around the world (examples include SRC, Beijer institute, Arizona State Univ., Tyndall, and organizations affiliated to the resilience alliance). In this approach the economic system is seen as a sub-system of the social system which in turn is a embedded in the ecosystem (biosphere). Human well-being is the normative goal, while economics and social processes provide tools for achieving it and the biosphere provides non-negotiable conditions and frames.

Human wellbeing is a somewhat broader term than human welfare, which is the normative goal in welfare economics. While ‘welfare’ is an economic term focusing on consumption and based on utilitarianism and mathematical optimization, ‘well-being’ is more interdisciplinary and include, besides consumption, also notions of freedom, equity and perceived fairness.

Sustainability can thus be defined as a condition where human well-being does not decrease over time. This definition is very general. It implies, for example, that the flow of goods and services from different types of capital contributing to well-being must be sustained over time. There are four broad types of capital: natural, physical, human and social. Natural capital includes everything from the biosphere - ecosystem goods, services and underlying functions - as well as minerals from the lithosphere. Physical capital include houses, infrastructures, all things produced by people. Human capital means knowledge; the better knowledge we have the more value we get from using natural and physical capital. Social capital is the level of trust and reciprocity in a society. The higher social capital, the higher our capacity to organize ourselves to innovate, adapt and transform towards more sustainability. Hence, both human and social capital are important to get as much sustained wellbeing as possible from the natural and physical capital stocks.

Historically most societies have degraded natural capital to invest in physical capital. Human well-being has increased in almost all parts of the world despite a degradation of natural capital, sometimes refered to as the “Environmentalist’s paradox”. Human capital has expanded through education. Social capital has changed in different directions and is generally associated with peace, democracy, equity, income level, income equality and low corruption. An important question is to what extent the different capital types are substitutable. How long can we continue degrading natural capital to enhance other types of capital and claim this will benefit future generations? This does not mean that all consumption included in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is unsustainable; some consumption patterns do not degrade natural capital. How tradeoffs are made between the different capital types in the interest of maximizing human well-being are the tasks of science and politics, or ultimately the task of every person.

Another important source of conflict is whether it’s ethical view ‘the environment’ as goods and services that people can consume according to their individual tastes, or if we have a moral obligation towards future generations to sustain the biosphere in a good condition.There have been various approaches used in an attempt to value nature. Scientific attempts to value nature are often based on the former: people are asked how much they are they willing to pay for various environmental goods and services. This assumes two things: the full substitutability of the goods and services and that sustainable development is a matter of choice by individual consumers. The second approach to valuation assumes that sustainable development is a matter of choice by citizens and that it concerns human rights issues, just like democracy. In political science, human rights and democracy are ‘overarching ideologies’ that people can agree on regardless of if they belong to the political left or right. These constitutional rights provide direction, frame and constraints to other legislation which in turn provide direction, frame and constraints to policy options as well as choices by consumers. Sustainable development has a very strong ethical foundation and it could, if we want, have the potential to be put in the same ‘constitutional’ category as democracy and human rights.

The sustainable development road map

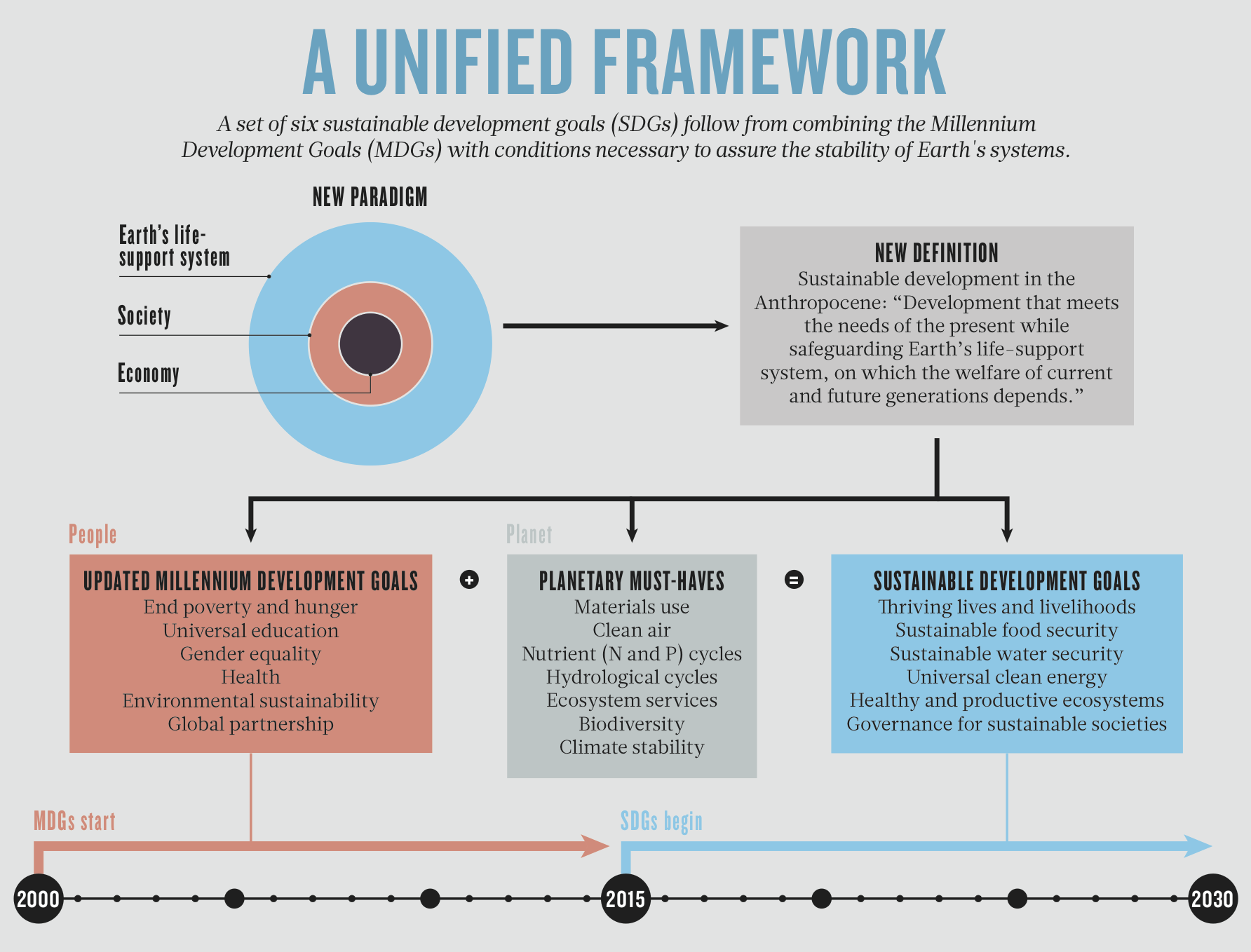

In 2012, the United Nations Rio+20 summit in Brazil committed governments to create a set of sustainable development goals (SDGs) that would be integrated into the follow-up to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). In an important paper in 2013, this was expanded to a unified framework to combine the goal of ending poverty and hunger within the constraints of the planetary system to provide the resources for this transition. It uses the important paradigm of integrated social-ecological systems that we presented in the previous section and provides a new roadmap for development towards 2030.

The sustainable development goals

This road map leads up to 17 ambitious sustainable development goals that in concert may provide the foundations for humanity in the anthropocene:

What is unique about these goals is the heavy focus on participatory approaches and stakeholder engagement during and after their establishment. Already in the Rio +20 meeting it was decided to pay particular reference to participation of vulnerable groups, such as women, developing countries, including African countries, least developed countries, land-locked developing countries, small-island developing States and middle-income countries to the decision-making process.

The ambitiousness has of course also gathered some critique, e.g. that the over 150 subtargets are way too many to be effectively monitored and that some need more aggressive pace since they are foundations for many of the other goals. Nevertheless, these goals provide an unprecedented collective effort for a sustainable future. Below I embed the UN site for the SDG and their descriptions (scroll down to have a look at all 17, click on them to expand their descriptions)

Tangible Sustainability goals

In this short Interview with Jeffrey Sachs, Director of The Earth Institute at Columbia University, he puts the new sustainability goals into a context and presents some of the challenges. Professor Jeffrey Sachs is widely considered to be the world’s leading expert on economic development and the fight against poverty. His work has been focused on ending poverty, promoting economic growth, fighting hunger and disease, and promoting sustainable environmental practices.

Contributors: Jon Norberg, Thomas Hahn

- Look through the sustainability goals.

- Which ones would you say are most known to the public such that they would affect everyday behaviour such as choice of products or ways of transportation

- Which ones feel far from everydays life and require substantial political will at national and global levels?

References

Griggs, David, et al. “Policy: Sustainable development goals for people and planet.” Nature 495.7441 (2013): 305-307.

Leave a Comment