Scenario Planning

Traditional landscape management is often built on the assumption that professional expertise and well-defined management goals will ensure efficient and effective management outcomes. However, such plans often fail to consider the variety of local issues, changing conditions over time and the propensity of new drivers of change to create extraordinary surprises (Peterson et al. 2003). Scenario planning is a systematic method for creatively analyzing complex futures. A scenario is an internally consistent and plausible narrative about the future that is informed by existing conditions and processes, as well as potential future ones (Enfors et al. 2008). Scenarios describe futures that could be instead of futures that will be, focusing on important uncertainties in the system rather than on the accurate prediction of a single outcome.

A key aspect of scenario planning is the focus on contrasts between several possible futures.

This highlights relationships between environmental factors, management choices, and system dynamics in a way that can inform decision-making (Peterson et al. 2003). Scenario analyses have been widely used over the past 50 years. Initially developed by response to the difficulty of creating accurate forecasts in the petroleum industry, one of the most well-known examples of scenario planning as a strategic management tool comes from the Shell Oil company, which in the early 1970s used scenario policy planning to respond to the 1970s oil crisis (Peterson et al. 2003). Scenario planning can take many different forms, and it is important to select a scenario planning process that fits the purpose of the project. Scenario-planning can be participatory or expert led to varying degrees (van Notten et al. 2003), and performed from local to global scales, or sometimes across scales (Biggs et al. 2007).

Below we describe a scenario planning process that was recently applied in Kenya (within the SPACES project - Sustainable Poverty Alleviation from Coastal Ecosystem Services) to explore possible futures for coastal communities dependent on local ecosystem services.

How to do scenarios?

The SPACES project use participatory models and scenarios with experts in poverty alleviation and sustainable resource management to: a) collaboratively develop a better understanding of the current and future changes in poverty and coastal ecosystems in coastal Kenya, and b) jointly develop a model for exploring policy interventions and their trade-offs.

Below follows a brief description of the 7 steps used for developing the scenarios within the SPACES project:

Step 1) Stakeholder analysis The SPACES project chose to develop scenarios through a participatory process conducted through a set of workshops. Therefore the first step was to identify relevant stakeholders (institutions, organisation and people of relevance to the coastal social-ecological systems studied) for the workshops to ensure a good representation of different values and knowledge’s. A Stakeholder Analysis was done by local experts following a criteria and ranking exercise to describe the stakeholders Importance (e.g. the extent to which a stakeholder’s wellbeing is either directly or indirectly affected by governance of and/or access to coastal ecosystems), Influence (e.g. a stakeholder’s level of agency to affect change in the management of coastal ecosystems and influence the livelihoods and wellbeing of stakeholders with a high importance) as well as the type of knowledge held by each individual.

Step 2) Problem orientation and boundary definitions The next step was to clearly define the scope as well as the spatial and temporal boundaries of the scenarios in focus. In this case the problem or question in focus was - “What will coastal ecosystems and levels of poverty alleviation look like in the future (2045)?”. The spatial boundary was defined as - From and including Mombasa to the Tanzanian border. It includes the seas and about 10 km inland. It includes urban and rural areas. It includes mangroves and coral reefs.” and the temporal boundary (which year to focus the future scenarios on) – “Year of 2045”.

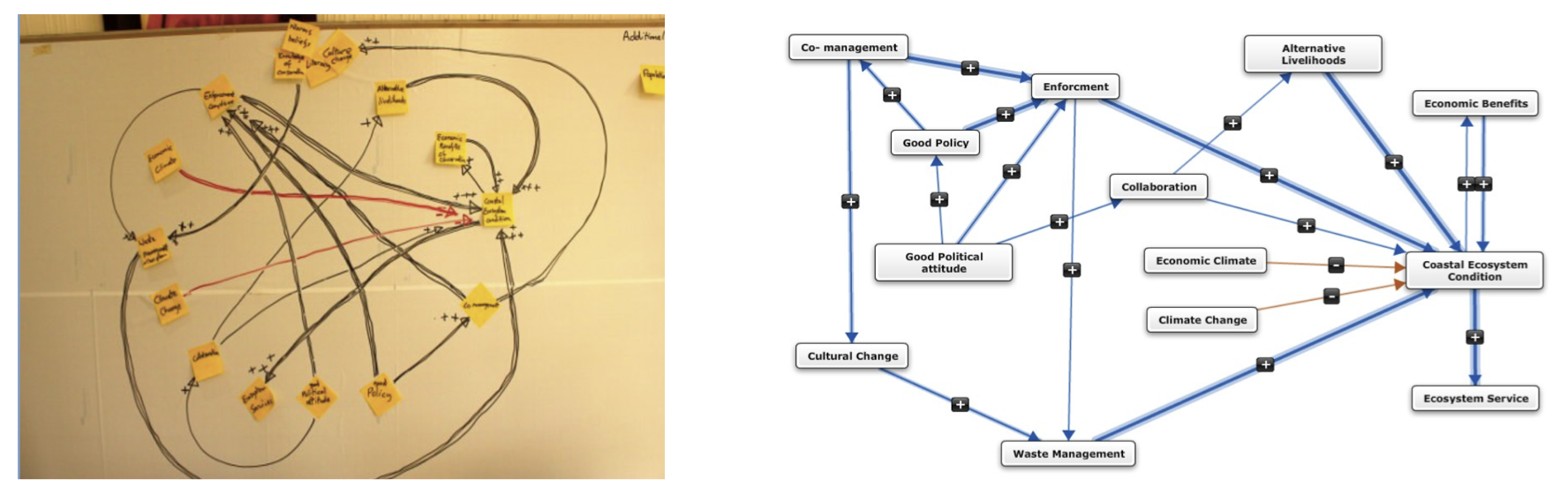

Step 3) Analysis of current system In the first day of the two day workshop a systems analysis was conducted with the participants to identify the major factors affecting the system: identify people, institutions, ecosystems and their connections. In this case Fuzzy Cognitive Maps* a semi-quantitative method akin to structural modelling was used (Fig. 1).

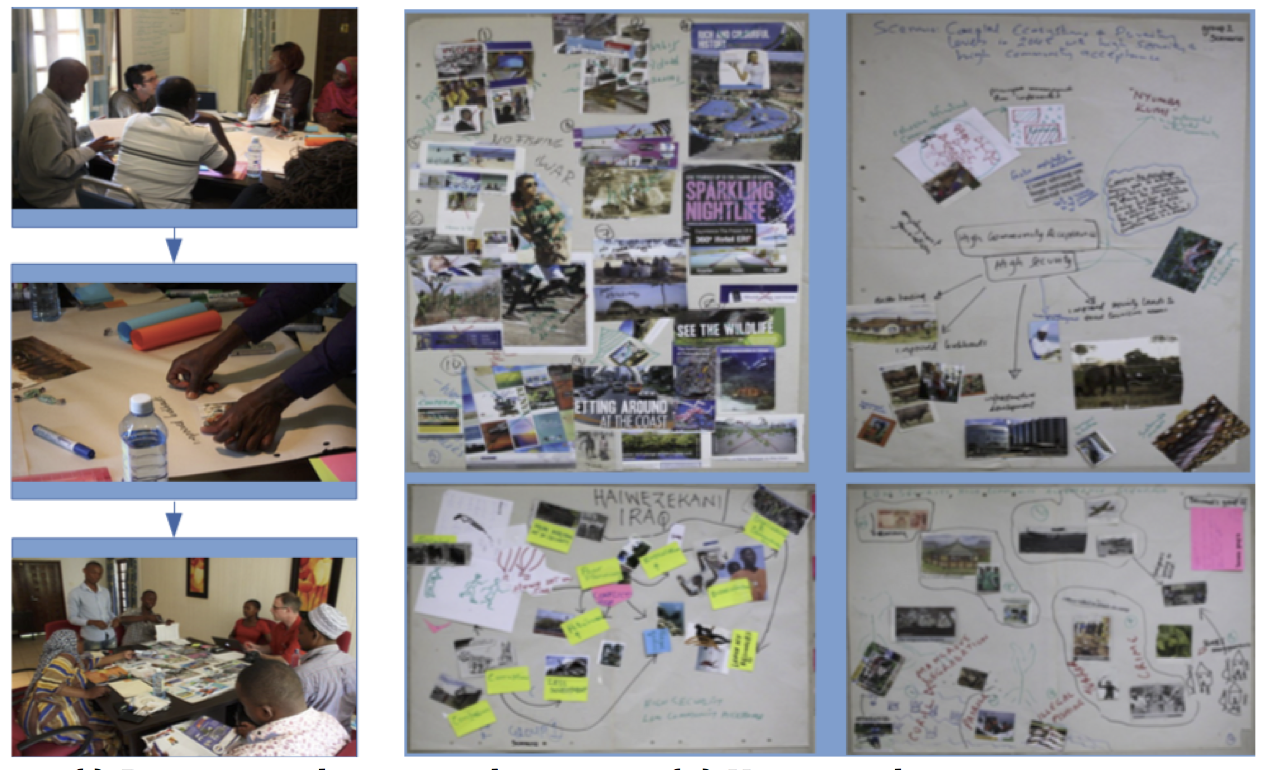

Step 4) Identify drivers of change In day two of the workshop, a three step process was followed to identify future drivers of change in the system (Fig. 2). i) First participants did an exercises to think about changes in the past and then they were asked to identify key drivers of change in 2045. Facilitators assisted the discussions to also make sure that “surprises” and “events” were added to the final round of factors shaping the future system. Finally participants were asked to: ii) score the most important drivers of change in the future, and iii) vote for the most uncertain of these drivers. The two drivers that scored highest in terms of importance and uncertainty were “security” and “community acceptance.”

Step 5) Development of exploratory scenarios The participants were asked to develop four future scenarios shaped by different combinations of the two drivers identified in the previous process:

1) High security, high community acceptance, 2) High security, low community acceptance, 3) Low security, high community acceptance, and 4) Low security, low community acceptance

in response to the question: “What will coastal ecosystems and levels of poverty alleviation look like in the future (2045)?” (Fig. 3). Finally the participants agreed on titles for their scenarios.

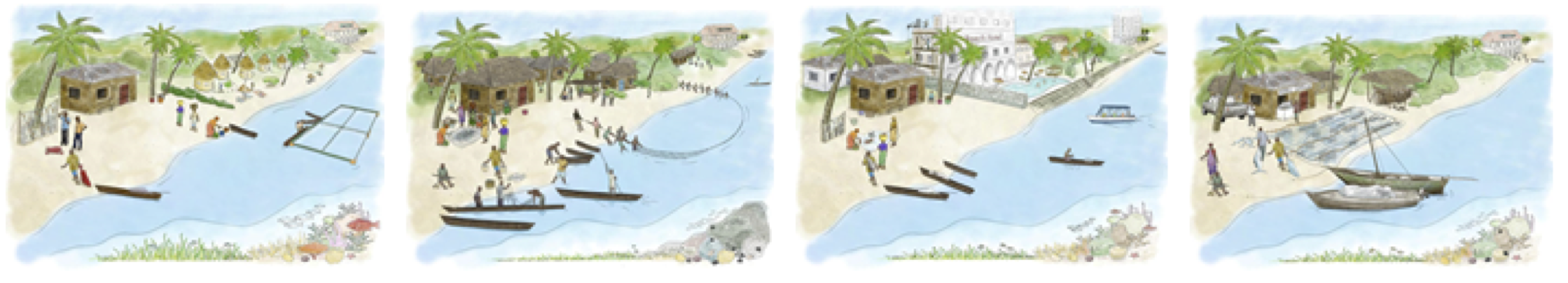

Step 6) Test, Refine and Use the scenarios Now the organising team will work in collaboration with artists to refine the scenarios and then present them at an upcoming workshop to give the participants a chance to react to and refine the scenarios as well as to get the chance to discuss trade-offs between different future scenarios, what future options to pursue and what traps to avoid. There are a number of different ways to present the outcomes of a scenario development process. One example of a final output from the P-Mowtick project is shown in Figure 4. The plan within the SPACES project is then to use the scenarios for example as a communication and discussion tool to inform policy (e.g. assess strategic choices in the light of different scenarios) and for future research.

How to use scenarios

Scenario planning can be used for various purposes, but in the context of social-ecological systems research it is often used to identify opportunities and threats associated with different future pathways, and thereby help navigate towards more desirable future while preparing for change (Enfors et al. 2008). One advantage of scenario planning is that it can incorporate a wealth of information from a variety of disciplines and knowledge systems, and although dealing with complex system dynamics, the outcome is often easily accessible for scientists as well as policy makers and lay people (Kok et al. 2007). Similarly, scenario planning can account for different values and perspectives on what attributes of a system are most important. By highlighting these different representations and values of the system, the scenario planning process can also become a platform for conflict resolution and increased collaboration between different groups of stakeholders. If organized and applied well, scenario-planning process can become a powerful tool for learning, consensus building (alignment of goals), and public action, which can make people better at preparing for and shaping their future (Wollenberg et al. 2000).

Note that the choice of FCMs was to fulfil other research objectives within SPACES and that less ambitious systems analysis tools could be used with the purpose to get a better systems understanding of the workshop participants.

References

Biggs, R., C. Raudsepp-Hearne, C. Atkinson- Palombo, E. Bohensky, E. Boyd, G. Cundill, H. Fox, S. Ingram, K. Kok, S. Spehar, M. Tengo, D. Timmer, and M. Zurek. 2007. Linking futures across scales: a dialog on multiscale scenarios. Ecology and Society 12(1): 17.

Enfors, E., Gordon, L.J., Peterson, G.D., Bossio, D., 2008. Making investments in dryland development work: participatory scenario planning in the Makanya catchment, Tanzania. Ecology and Society 13 (2), 42.

Kok, K., R. Biggs, and M. Zurek. 2007. Methods for developing multiscale participatory scenarios: insights from southern Africa and Europe. Ecology and Society 12(1): 8.

Peterson, G. D., G. S. Cumming, and S. R. Carpenter. 2003. Scenario planning: a tool for conservation in an uncertain world. Conservation Biology 17(2):358–366.

van Notten, P. W. F., Rotmans, J., van Asselt, M. B. A. and Rothman, D. S. (2003). An updated scenario typology, Futures, 35 (5), 423-443.

Wollenberg, E., Edmunds, D. and Buck, L. (2000). Using scenarios to make decisions about the future: anticipatory learning for the adaptive co-management of community forests, Landscape and Urban Planning, 47(1–2), 65-77.

Internet: SPACES: . Accessed 02-03-2015. 12.27.

P-Mowtick: Accessed 02-03-2015. 12.28.

Contributors

Matilda Thyresson

Leave a Comment