Building Knowledge

The Multiple Evidence Base (MEB) is an approach for connecting knowledge systems, building dialogue and mobilizing existing knowledge for assessments and improved policy, such as within IPBES. It is also a way to support and enhance existing mechanisms for learning and decision-making in response to the dynamics of social-ecological systems at all scales.

This text is taken from the SRC knowledge fact sheet

Indigenous and local knowledge systems are increasingly recognized and brought forward as sources of understand- ing on ecosystem dynamics, sustainable practices, and interdependencies between people and nature; a potential that often has not informed decision making on ecosystem management beyond the local level. In some regions and at some temporal and spatial scale, our sole source of knowledge may reside among local users and managers. However, there has so far been limited success in bringing knowledge systems together beyond case studies.

Furthermore, the actors and knowledge systems that generate and underpin knowledge and insights are often not part of decision-making processes. Thus, there is a great need to develop functioning mechanisms to engage and legitimate in a transparent and constructive way synergies between knowledge systems (Reid et al. 2006).

The Multiple Evidence Base is an approach that pro- poses parallels whereas indigenous, local and scientific knowledge systems are viewed to generate equally valid, complementarily and useful evidence for interpreting conditions, change, trajectories, and in some cases causal relationships relevant to the sustainable governance of ecosystems and biodiversity (Tengö et al. 2013). The approach draws on literature emphasizing the complementary nature of various knowledge systems, as well as the need to move away from translating knowledge into one currency, i.e. “integrating” indigenous and local knowledge into science through unidirectional validation processes (Berkes 2007, Nadasdy 1999).

It also draws on the outcomes of a dialogue process in collaboration with a network of indigenous peoples and local communities, in particular the International Indigenous Forum for Biodiversity (IIFB) (see www.dialogueseminars. net/panama). The starting point in the Multiple Evidence Base approach is that each system contributes to knowledge relevant to the sustainable management of ecosystems – through its own unique practices and experiences, complementarities as well as new ideas, and innovation from cross-fertilization across knowledge systems.

All these are valid and need to be build upon in e.g. assessments and policy decisions related to biodiversity and ecosystem services. The type of contribution may vary according to the problem at hand, including the extent to which it may apply. However, to realize this potential, we argue that different criteria of validation should be applied to data and information originating from different knowledge systems. The MEB approach highlights the importance of indigenous and local knowledge systems on their own terms, i.e., validated within rather than by pre-defined science criteria. It also recognizes differences within different types of scientific knowledge, such as social science and natural science disciplines, and forms of evidence.

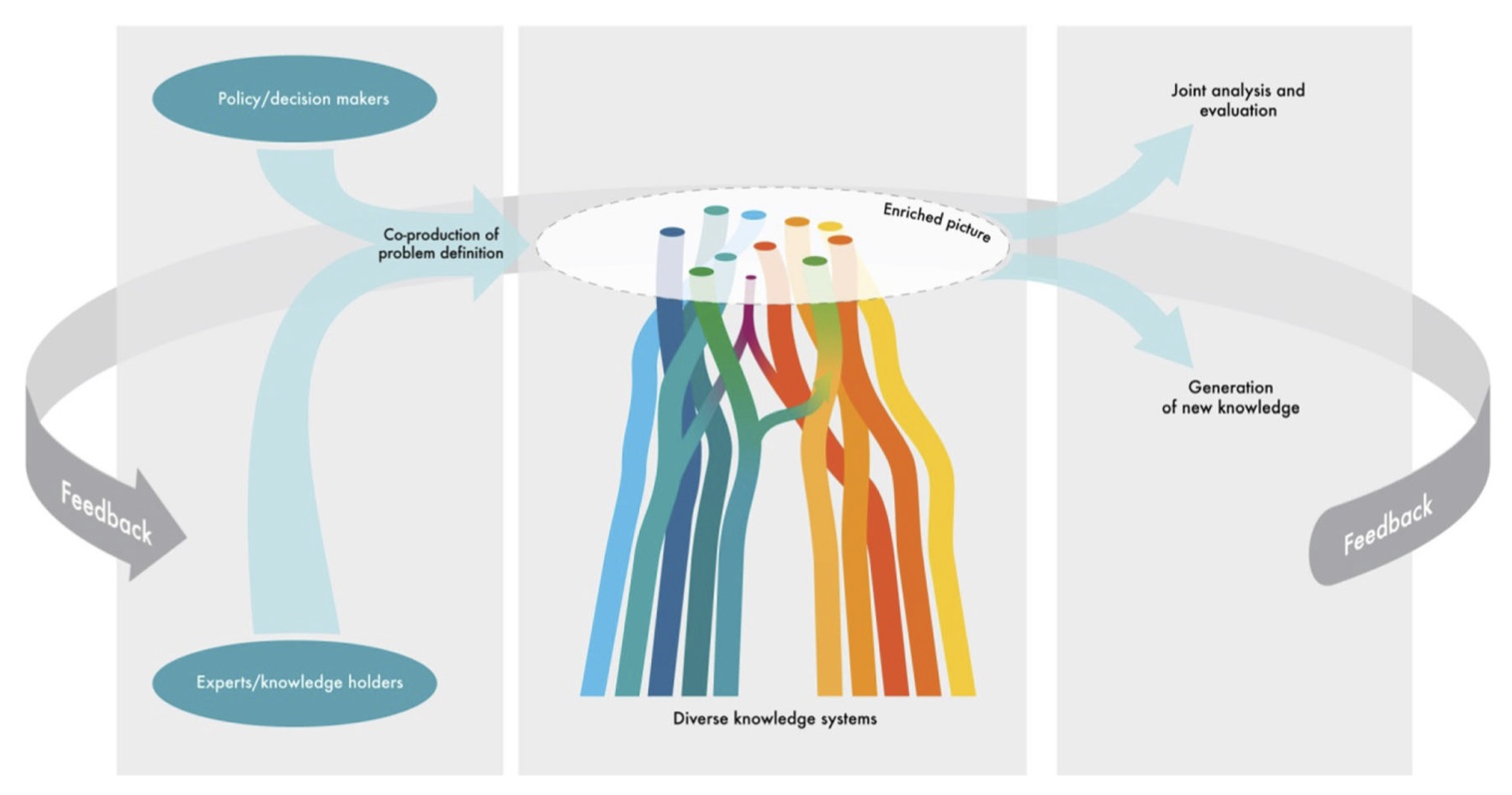

This process allows for an enriched picture to emerge based on the triangulation of information across knowledge systems and thus evaluation of the relevance of knowledge and information at different scales and in different contexts. Brought together, multiple evidence on an issue or assessment topic, such as Arctic sea ice dynamics related to climate change, will create an enriched picture of understanding in an assessment process. The enriched picture is also a starting point for further knowledge generation, within or across knowledge systems through cross-fertilization and co-production of knowledge. This is outlined in Figure 1.

We propose the MEB as a ‘nested approach’ that considers different types of knowledge (from very specific and localized to more general) and different types of overlap between knowledge systems that may appear at different levels (and for different goals). Parallel approaches to addressing complementarities, potential synergies as well as contradictions across knowledge systems have been applied across the globe and for various issues, for example sea ice dynamic and climate change (Laider 2006), population dynamics of fish and other wildlife (Mackinson 2001, Moller et al. 2004, Gagnon & Berteaux, 2009), as well as land use change and farming practices (Chalmers and Fabricius 2007, Brondizio 2008)

Many of the case studies find that a MEB approach creates an opportunity for “a culturally informed” appraisal of scientific knowledge and practice (IPBES, 2012). For example, it has been shown that combining scientific and traditional methods for monitoring wildlife provides an opportunity for customary users to scrutinize science and for science to learn relationships and processes previously unknown (Moller et al. 2004). Thus, in addition to broadening and enhancing the available sources of relevant knowledge as base for decision making, a MEB approach aims at enhancing trust and avoiding the arrogance of a single ex ante “right approach,” which frequently overrides the contribution of indigenous peoples, local communities, and practitioners in the context of assessment programs and development projects.

An on-going knowledge platform that uses a MEB approach is the Community Based Monitoring and Information Systems (CBMIS), a bottom-up process for mobilizing indigenous and local knowledge for monitoring of biodiversity, ecosystems, and human wellbeing. CBMIS refers to the bundle of monitoring approaches related to biodiversity, ecosystems, land and waters, and other resources, as well as human well-being, used by indigenous peoples and local communities as tools for their management and documentation of their resources. CBMIS is a joint initiative among a global network of indigenous peoples and local communities, which seeks to combine the monitoring needs of communities with need for detailed data as a base for joint action related to territories and resources. The initiative emerged in cooperating with the CBD Secretariat and the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. Initially, regional and thematic workshops have been organized to identify indicators relevant for indigenous peoples, towards monitoring local to global progress in achieving internationally agreed environment and devel- opment goals, such as the indicators related to traditional knowledge for the Aichi biodiversity targets. The network is now advancing in developing tools and methods to a common set of instruments that can be used by communities. (SCBD, 2013; Stankovich, M. et.al, 2013).

To realize a MEB approach in e.g. assessments process- es, there is a need for true dialogues, which gives and promotes credibility and legitimacy of all involved. This requires a process whereas the problem definition, the assessment process, and the evaluation of findings involve co-production and collaboration with relevant stakeholders from the onset. As part of this, there is a need for innovative ways for dialoguing and meeting, as well as new tools and understanding of e.g. combining qualitative and quantitative data and scaling knowledge across scales.

A MEB approach should be tailored in relation to different goals, regions, and kinds of assessment and scales of investigation, but also needs to recognize cross-scale interactions.

Contributors

Maria Tengö, Pernilla Malmer, Thomas Elmqvist, Stockholm Resilience Centre Eduardo S. Brondizio, Indiana University, Marja Spierenburg, VU University Amsterdam

References

Berkes, F. (2007). Sacred Ecology (2nd ed., p. 336). New York: Routledge.

Brondizio, E. S. (2008). Amazonian Caboclo and the Acai Palm: Forest Farmers in the Global Market. (p. 402). New York: The New York Botanical Garden Press.

Chalmers, N., & Fabricius, C. (2007). Expert and Generalist Local Knowledge about Land-cover Change on South Africa’s Wild Coast: Can Local Ecological Knowledge Add Value to Science ? Ecology And Society, 12(1), 10.

Gagnon, C. A., & Berteaux, D. (2009). Integrating Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Ecological Science : a Question of Scale. Ecology and Society, 14(2).

Huntington, H. P., Suydan, R. S., & Rosenberg, D. H. (2004). Traditional knowledge and satellite tracking as complementary approaches to ecological understanding. Environmental Conservation, 31(3), 177–180.

IPBES.(2012) Consideration of initial elements: recognizing indigenous and local knowledge and building synergies with science UNEP/IPBES/1/INF/5

Laidler, G. J. (2006). Inuit and Scientific Perspectives on the Relationship Between Sea Ice and Climate Change: The Ideal Complement? Climatic Change, 78(2-4), 407–444.

Mackinson, S. (2001). Integrating Local and Scientific Knowledge: An Example in Fisheries Science. Environmental Management, 27(4), 533–545. Moller, H., F. Berkes, P. O. Lyver, and M. Kislalioglu. 2004. Combining science and traditional ecological knowledge: monitoring populations for co-management. Ecology and Society 9(3): 2.

Nadasdy, P. (1999). Politics of TEK: Power and the “integration” of knowledge. Arctic Anthropology, 36(1-2), 1–18.

Neis, B., Schneider, D. C., Felt, L., Haedrich, R. L., Fischer, J., & Hutchings, J. a. (1999). Fisheries assessment: what can be learned from interviewing resource users? Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 56(10), 1949–1963.

Reid, W. V., Berkes, F., Wilbanks, T., & Capistrano, D. (2006). Bridging Scales and Knowledge Systems: Concepts and Applications in Ecosystem Assessment (p. 345). Island Press.

SCBD. (2013). Indicators relevant for traditional knowledge and customary sustainable use. UNEP/CBD/WG8J/8/9

Stankovich, M. Chico Cariño, C., Regpala, M.E., Guillao, J.A., Balawag, G. (2013) Developing and Implementing Community-Based Monitoring and Information Systems: The Global Workshop and the Philippine Workshop Reports. Tebtebba Foundation.

Tengö, M., Brondizio, E. S., Elmqvist, T., Malmer, P. & Spierenburg, M. Connecting Diverse Knowledge Systems for Enhanced Ecosystem Governance: The Multiple Evidence Base Approach. Ambio (2014). Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, Sweden.

Leave a Comment