Bridging and brokering

Ecosystems do not abide by human-made jurisdictions and administrative borders, and it is therefore not possible or feasible to divide them into separate, self-supporting, autonomous components. Furthermore, many of the services they provide are common pool resources with multiple actors competing for use, often leading to resource depletion or management conflicts (Hardin 1968). Hence, management of any given resource would benefit from actors agreeing on common rules and practices, coordinating usage, engaging in conflict resolution, negotiating various tradeoffs, sharing information, and building common knowledge (Folke et al. 2005). Research shows that top-down centralized management is poorly suited for this (Holling & Meffe 1996; Folke et al. 2005). Attention has therefore been directed at governing systems where multiple actors to various degrees are involved in the governing processes. However, making multiple actors collaborate is not a trivial task (Ansell & Gash 2007).

Recent research has identified the existence of often informal social networks as a common and important denominator in cases where different stakeholders have come together to effectively deal with natural resource problems and dilemmas (Scholz & Wang 2006). Having a large group of actors connected through a collaborative social network does not, however, by itself imply that collaboration will be effective. This for example applies if the group is large and coordinating activities among a large set of actors therefore becomes challenging (Provan & Kenis 2007). This lead to an increasing recognition of agency and leadership (Westley et al. 2013).

In the context of resource management, where the managed ecosystems span across boundaries, this becomes increasingly challenging since the actors typically are quite different (fishermen, government agencies, private corporations, NGOs, etc.). Bringing such a heterogeneous set of actors together is a different challenge compared to coordinating actors of the same type. This is where the notion of bridging and brokering organizations becomes particularly relevant. A bridging organization is an organization that brings a diverse (and often large) set of actor together. This is typically achieved through informal structures of collaborations, often relying on social (organizational) networks (Hahn et al. 2006). In the next section we provide an example of how a bridging (brokering) organization help to achieve a substantial reduction of unregulated, unreported and illegal fishing in the Southern Ocean, by effectively coordinating a diverse set of actors and functions.

Making collaboration work

The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) was established in 1983 with a mandate to manage fish stocks and associated ecosystem components in the Southern Ocean (excluding marine mammals, which are governed by other mechanisms). CCAMLR member states include countries with Antarctic claims, with nationally sovereign territories (Sub-Antarctic islands) and other countries with research or fishing interests in the region. CCAMLR was established after the substantial depletion of several species of whales and finfish, and during a period when there was a rapid increase in the interest to harvest Antarctic krill (Österblom & Sumaila 2011).

The waters around Antarctica (the area managed by CCAMLR) became an increasingly interesting frontier for natural resource extraction following the collapse of several populations of predatory fish stocks in the Northern hemisphere (including the Newfoundland cod). A number of vessels previously engaged in e.g., tuna fishing started to appear in the CCAMLR area – several of which had no license to fish in this region. The vessels were primarily catching Patagonian toothfish, a cod-like predatory fish which was gaining popularity, for the US market. Analyses by CCAMLR scientists showed that such illegal fishing was several times higher than the small, but developing licensed catch of toothfish, and there was a substantial risk of stock collapses. Toothfish were caught on long-lines with baited hooks, which also caught globally threatened albatross seabirds. Scientific estimates indicated that such catches were at a level where these populations were severely threatened.

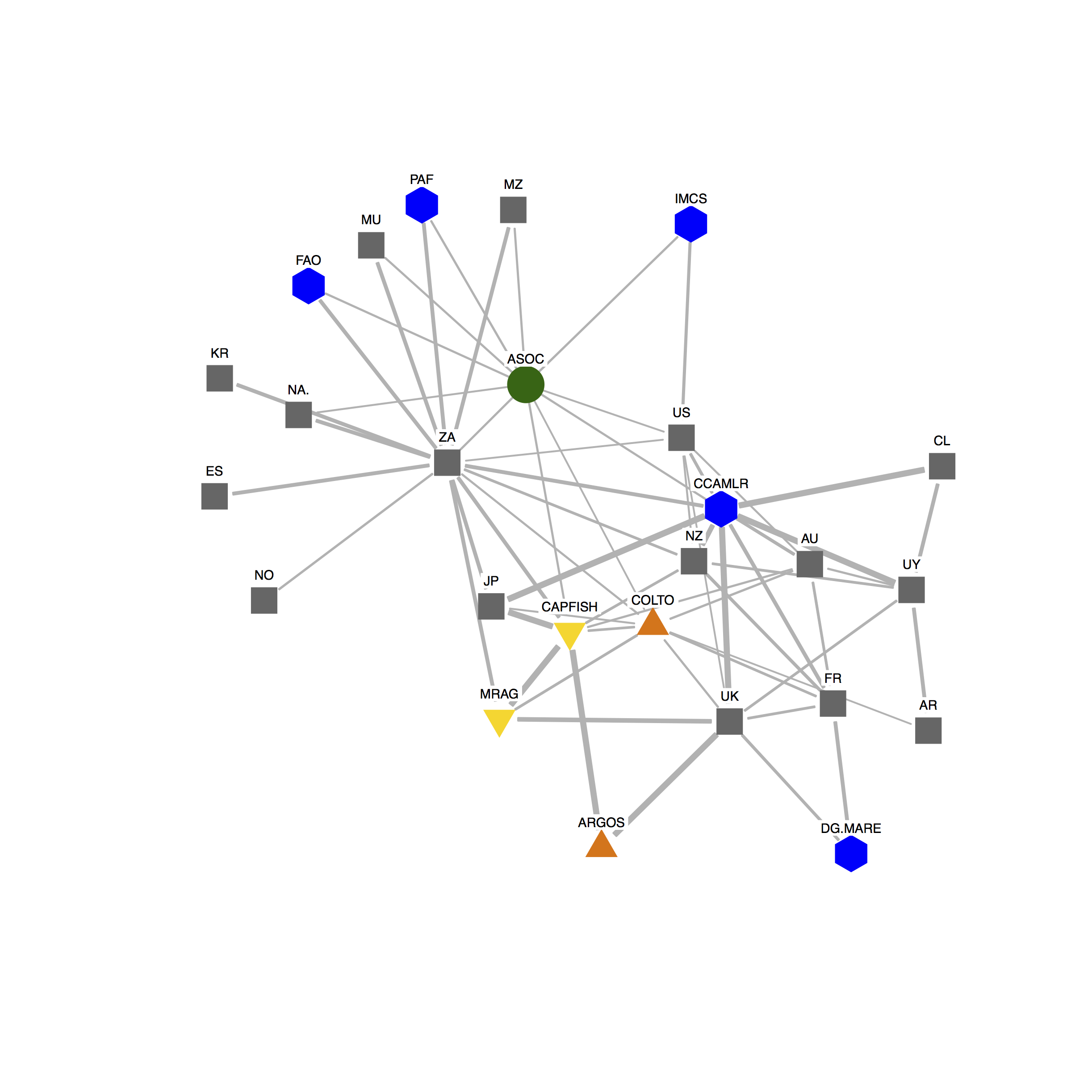

Based on data collected from environmental NGOs, it was clear that several vessels operating illegally in the CCAMLR area were flagged to CCAMLR member states, which means that they have the responsibility for them. This created a sensitive political situation and it became increasingly clear that CCAMLR, an organization where decisions are taken in consensus, would be unable to effectively develop policy measures to address the problem. Instead, environmental NGOs, in collaboration with the licensed fishing industry, mobilized to collect more information on illegal operators, engaged in monitoring activities and developed alternative policy measures. The information collected was published in local newspapers (where known illegal operators lived), fishing media outlets and in reports presented to CCAMLR by NGO-observer organizations. Thus, they established themselves as broker organizations making critical information available to both member states and the general public at that specific point in time. These informal naming and shaming strategies initially proved very effective and led to a reduction of illegal fishing activities. However, a few years later, illegal fishing levels increased again. This time, the license industry was better organized and took on the role as data collector and information sharer. The industry established the Coalition Of Legal Toothfish Operators (COLTO), and was able to gain observer status to CCAMLR. Through similar naming and shaming strategies and political lobbying, COLTO was able to contribute substantially to a second reduction of illegal fishing.

The political pressure that NGOs and the industry had mobilized, the information that they had collected and the proposals for policy measures that they had developed, contributed to the necessary decisions in CCAMLR. The Commission agreed on developing an illegal blacklisting of vessels, established an electronic traceability system for toothfish catches and a joint vessel monitoring system. These actions together enabled the CCAMLR secretariat to operate as an officially sanctioned bridging (broker) organization, with formal protocols for how to use and distribute information coming from governments, environmental NGOs and the licensed industry. The secretary thus act as the “spider in the web” bringing all these actors closer together.

References

Ansell, C. & Gash, a. (2007). Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory, 18, 543–571.

Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P. & Norberg, J. (2005). Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour., 30, 441–473.

Hahn, T., Olsson, P., Folke, C. & Johansson, K. (2006). Trust-building, Knowledge Generation and Organizational Innovations: The Role of a Bridging Organization for Adaptive Comanagement of a Wetland Landscape around Kristianstad, Sweden. Hum. Ecol., 34, 573–592.

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tradgedy of the Commons. Science (80-. )., 162, 1243–1248.

Holling, C.S. & Meffe, G.K. (1996). Command and control and the pathology of natural resource management. Conserv. Biol., 10, 328–337.

Provan, K.G. & Kenis, P. (2007). Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory, 18, 229–252.

Scholz, J.T. & Wang, C.-L. (2006). Cooptation or Transformation? Local Policy Networks and Federal Regulatory Enforcement. Am. J. Pol. Sci., 50, 81–97.

Westley, F.R., Tjornbo, O., Schultz, L., Olsson, P., Folke, C., Crona, B.I. & Bodin, Ö. (2013). A Theory of Transformative Agency in Linked Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc., 18, art27.

Österblom, H. & Bodin, Ö. (2012). Global Cooperation among Diverse Organizations to Reduce Illegal Fishing in the Southern Ocean. Conserv. Biol., 26, 638–648.

Österblom, H. & Sumaila, R. (2011). Toothfish crises, actor diversity and the emergence of compliance mechanisms in the Southern Ocean. Glob. Environ. Chang., 21, 972–982.

Contributors

Örjan Bodin and Henrik Österblom

Leave a Comment