Agency and transformation

Agency describes the capacity of an agent (e.g. a human) to act in its surrounding world.

In research on resilience, the concept has become highly relevant for studying the role of key individuals in bringing about transformations for sustainability (Westley et al. 2013). The importance of individual agency has been highlighted in several evaluations of the factors leading to shifts to ecosystem-based and adaptive management (Fabricius et al. 2007). But sustainability transformations are not just the product of a single individual’s vision and steering; rather, they require systemic shifts in institutional underpinnings such as mental models, management routines, and resource flows (Westley et al. 2013). Such shifts are often multilevel and multiphase processes, involving a variety of actors pursuing strategies that are attuned to opportunities arising from dynamic changes occurring within the system they are seeking to transform.

One current field of research is the relationship between different strategies and techniques actors utilize, and the broader system dynamics that shape the context in which they are working. This research emerges from research on linked social-ecological systems (Olsson et al. 2004) and connect these to literature on entrepreneurship (social, policy, and institutional), which examines the role of strategic agency in the transformation of complex adaptive systems generally (Westley et al. 2006).

The notion that individual agency can be vital in shaping the dynamics of broader systems taps into a long-running debate in the social sciences about the primacy of leadership versus non-directed, iterative change in causing systemic shifts (Emirbayer and Mische 1998). The literature on SES straddles this divide. It contains forceful arguments that complex social-ecological systems cannot be governed by the top-down, command and control forms of management sometimes associated with conventional ideas of leadership (Gunderson et al. 1995). At the same time, SES research contains case studies showing strong evidence of the role of individual agency in achieving transformations from less adaptive to more adaptive management and governance systems (Olsson et al. 2006). This incongruity, in which one set of observations suggests that conventional leadership of SES is ineffectual and another identifies agency as a crucial factor in transformations for adaptability, suggests a new framework is needed to explain the role of agency in SES transformation.

In the literature, the individuals who “make it happen” have been identified as champions, policy entrepreneurs, facilitators, dedicated energetic individuals, change agents, organizational entrepreneurs, brokers, knowledgeable individuals or stewards, social innovators, and transformative or visionary leaders (Westley et al. 2013). Ultimately, it is questionable whether leadership is the appropriate word for the activity of change agents in such a complex domain of networks, sectors, and scales.

Drawing on a set of case studies, Folke et al. (2003) tested this assumption in SES, and identified numerous actor groups engaged in their stewardship: knowledge carriers and retainers, stewards and leaders, interpreters and sense makers, networkers and facilitators, visionaries and inspirers, innovators and experimenters, and followers and reinforcers. These change agents demonstrate a variety of skills seemingly required for transforming such complex, linked systems.

Agency, entrepreneurship, and/or stewardship

The findings from the field of ecosystem stewardship are echoed in the small but growing body of work in management and organizational studies concerned with the role of strategic agency in complex and interorganizational domains (Westley et al. 2006). Like the SES literature, this research explores agency at the broad system scale, in what might be termed the “problem domain”. A problem domain is made up of the actors, organizations, and institutions concerned with or affected by a particular complex problem, and thus includes actors working at different organizational, jurisdictional, and geographic scales. When exploring the transformation of ecosystem management, the problem domain involves the local communities, management agencies, NGOs, corporations, government actors, indigenous groups, scientists, and actors who are invested in the future of that ecosystem, and provides a useful term to describe the social aspect of an SES.

The literature on agency in such problem domains argues that strategic agency is pivotal in moving a process of transformation forward. Within complex problem domains, however, strategic agency is typically not associated with just one individual, rather is produced through the strategies of a number of actors, each of whom takes actions that help the system progress through different stages of innovation and transformation (Westley et al. 2013). This kind of effort is more precisely defined as “institutional entrepreneurship,” a concept developed first by DiMaggio (1988) to describe the efforts of individuals who seek to change the institutions governing a particular domain in the interests of realizing particular goals of their own.

Shifting from the notion of leader to that of entrepreneur usefully moves focus from the leader-follower relationship to the endeavor itself, and to the imperative of seizing opportunities and mobilizing resources that will gain support for innovations critical to transformations of social-ecological systems. Similarly, shifting the focus to the institutional level from the organizational leader allows us to see the importance of cross-scale interactions and the challenge of transforming the value system, economic system, and political system that supports non-sustainable approaches to ecosystem stewardship. This focus is more in keeping with our understanding of emergence and change in complex adaptive systems (Westley et al. 2006). We will therefore refer to institutional entrepreneurs in our discussion of agency for transformation in complex social-ecological systems.

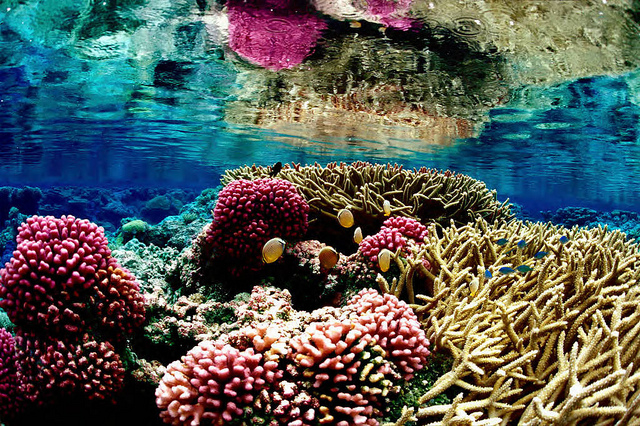

The coral reef triangle

Rosen and Olsson (2013) have investigated the role of institutional entrepreneurs in the emergence of the Coral Triangle Initiative. Such entrepreneurs are “individuals and groups of individuals who leverage resources to create new institutions or transforming existing ones”. The Coral Triangle is a unique marine area and a biodiversity hot spot located in the Western Pacific Ocean. More than 120 million people live in the Coral Triangle and rely on its coral reefs for food, income, protection from storms and a number of other ecosystem services. In 2007 the Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI) was formed as a multilateral partnership of six countries to address the urgent threats facing these unique coastal and marine ecosystems.

Rosen and Olsson investigate the dynamic process leading up to the establishment of the CTI. It includes the Indonesian president, a series of international conferences, NGOs, donor agencies, informal networking, trust building, lobbying and diplomacy. They all interacted over a period which can be divided into four different phases. The transition from one phase to another was enabled by certain key events. Phase one introduced the new idea of the CTI to the highest political level by drawing on formal and informal networks. It was followed by a second phase focused on mobilizing funds and support, in collaboration with President Yudhoyono who officially initiated the partnership. In phase three the preparing for the first high-level meeting between the six countries was given central attention. This included conceptualizing what the CTI could look like and preparing drafts of central steering documents. This proved to be key to succeed in the fourth phase where the deal was sealed during a whole series of multilateral and national meetings, arranged to develop legal and financial arrangements necessary to implement the initiative.

The study revealed that a small network of approximately ten institutional entrepreneurs was key to initiate the process. They developed the scientific concept of the CTI into an integrated framework for marine governance. This framework not only requires the six states to multiply their cooperation and carry out far-reaching institutional reforms, but also a mind shift — viewing ecosystem-based management and marine conservation not primarily as a cost, but rather as an investment in sustainable economic development and national security. These ten entrepreneurs came from both inside and outside the region and predominantly, but not solely, from conservation NGOs with a long history of working with marine conservation. They all had extensive experience in dealing with resource challenges or with bringing governments and non-state actors together for better marine conservation. Moreover, it was revealed that all of them had advisory or managerial positions in their organizations, meaning that they could access financial resources and use already existing local to global networks to scale up their ideas. The study concludes that institutional entrepreneurs can only succeed by interacting with other forms of leadership, such as the strategic leadership of the Indonesian President Yudhoyono or the orchestrated action of donor agencies and international NGOs.

On another level, the process of developing the CTI has been triggered by a number of underlying driving forces, including demands for social and economic development, concerns about political stability and national security, and rapid loss of biodiversity — particularly commercially important species. Together these factors seem to have opened a window of opportunity for the new institutional arrangements for ecosystem-based management and regional cooperation to emerge. Institutional entrepreneurs played a crucial role by aligning factors and showing the interconnectedness between social and ecological goals. In particular, it seems like the support from the six countries of the CTI is based on the initiative’s connection to a range of security concerns, revolving around things like food crises, economic deprivation, terrorism and illegal fishing.

In conclusion, the study emphasises that institutional entrepreneurs must both understand and develop strategies to link security issues, environmental change, and ecosystem-based management. This was key to the success to leverage support and resources to create new institutions and transform existing ones in the emergence of the Coral Triangle Initiative.

References

DiMaggio, P. 1988. Interest and agency in institutional theory. Pages 3-22 in L. Zuker, editor. Institutional patterns and organizations: culture and environment . Ballinger, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. What is agency? American Journal of Sociology 103(4):962-1023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/231294

Fabricius, C., C. Folke, G. Cundill, and L. Schultz. 2007. Powerless spectators, coping actors, and adaptive comanagers: a synthesis of the role of communities in ecosystem management. Ecology and Society 12(1): 29. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss1/art29/

Folke, C., J. Colding, and F. Berkes. 2003. Synthesis: building resilience and adaptive capacity in social-ecological systems. Pages 352-387 in F. Berkes, J. Colding, and C. Folke, editors. Navigating social-ecological systems: building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511541957.020

Gunderson, L. H, S. S. Light, and C. S. Holling. 1995. Barriers and bridges to the renewal of regional ecosystems. Columbia University Press, New York, New York, USA.

Olsson, P., C. Folke, and T. Hahn. 2004. Social-ecological transformation for ecosystem management: the development of adaptive co-management of a wetland landscape in Southern Sweden. Ecology and Society 9(4): 2. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss4/art2

Olsson, P., L. H. Gunderson, S. R. Carpenter, P. Ryan, L. Lebel, C. Folke, and C. S. Holling. 2006. Shooting the rapids: navigating transitions to adaptive governance of socialecological systems. Ecology and Society 11(1): 18. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art18/

Rosen, F., and P. Olsson. 2013. Institutional entrepreneurs, global networks, and the emergence of international institutions for ecosystem-based management: the Coral Triangle Initiative. Marine Policy 38:195-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2012.05.036

Westley, F., B. Zimmerman, and M. Q. Patton. 2006. Getting to maybe: how the world is changed . Random House, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Westley, F. R., O. Tjornbo, L. Schultz, P. Olsson, C. Folke, B. Crona and Ö. Bodin. 2013. A theory of transformative agency in linked social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society 18(3): 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-05072-180327

Contributors

Per Olsson and Lisen Schultz

Leave a Comment