Institution

“Institutions are any kind of practices or organizations put in place or emergent from past interactions that affect all forms of repetitive and structured interactions between people.”

Rules, norms, shared strategies (habits relating to interactions with other people) fall under the umbrella of institutions. They become “weaker” in the order of rules>norms>strategies meaning that the degree of sanctioning when breaking a strategy for example, is less than for breaking a norms. Institutions are human constructs and they can change over time due to reinterpretation or rewriting.

Some examples:

- Markets are institutions that organize the transfer of goods and services

- Laws are rules made by the governing body and enforced with sanctioning

- Norms can be unspoken and do not have formal sanctioning. An example is cleaning kitchen after you use it at work. It is expected, but usually there is no formal “kitchen police” even though social pressure can be just as effective

- Holding to your right as a pedestrian can be a strategy, i.e. it is not stated explicitly nor sanctioned if broken, but it can simplify pedestrian traffic in crowded places

To dissect the nature of institutions, let’s look at the components of a rule:

- It defines for whom the rule applies

- It has request, i.e. must, may or must not

- It has an aim, e.g. to make people stop their cars at red light.

- It defines under what conditions

- It sets out the consequence of not conforming to the rule

For a formal enforced rule all 5 components must be known. Typically, for a norm, the last (5: consequence) is often not defined. For a strategy, the second (2: request) is also omitted. Think of a rule that you obey, and try to “dissect” it according to these components. Why would you dissect a rule? Well, it makes it easier to compare how rules are enforced in different situations or areas around the world. For example, there are hundreds of different rules on how one can gather wood for fuel in communal used forests. Being able to compare exactly how they differ and what aspects of rules lead to sustainable use can be very valuable.

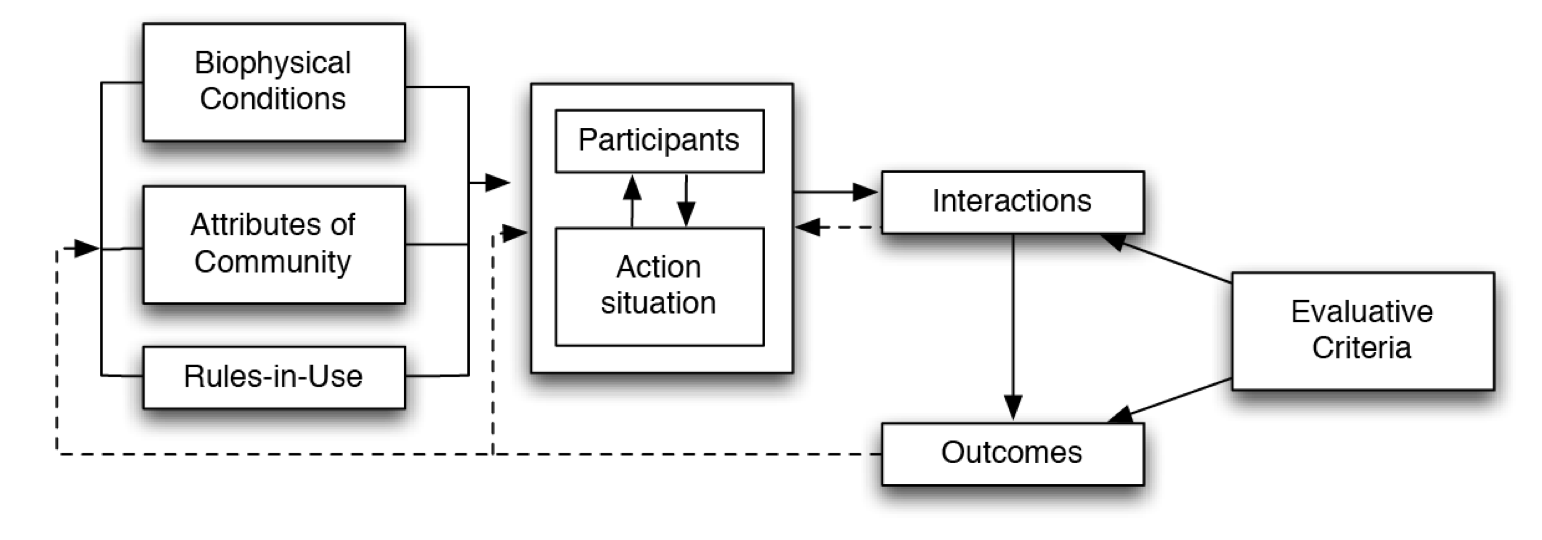

The institutional dynamics framework

Elinor Ostrom, the nobel laureate in economics 2009, termed situations in which people organize to regulate behavior as action arenas. This term is not commonly used in all disciplines of sustainability science, but here we can define it as an action arena occurs whenever individuals interact, exchange goods or solve problems, i.e. most social interactions.

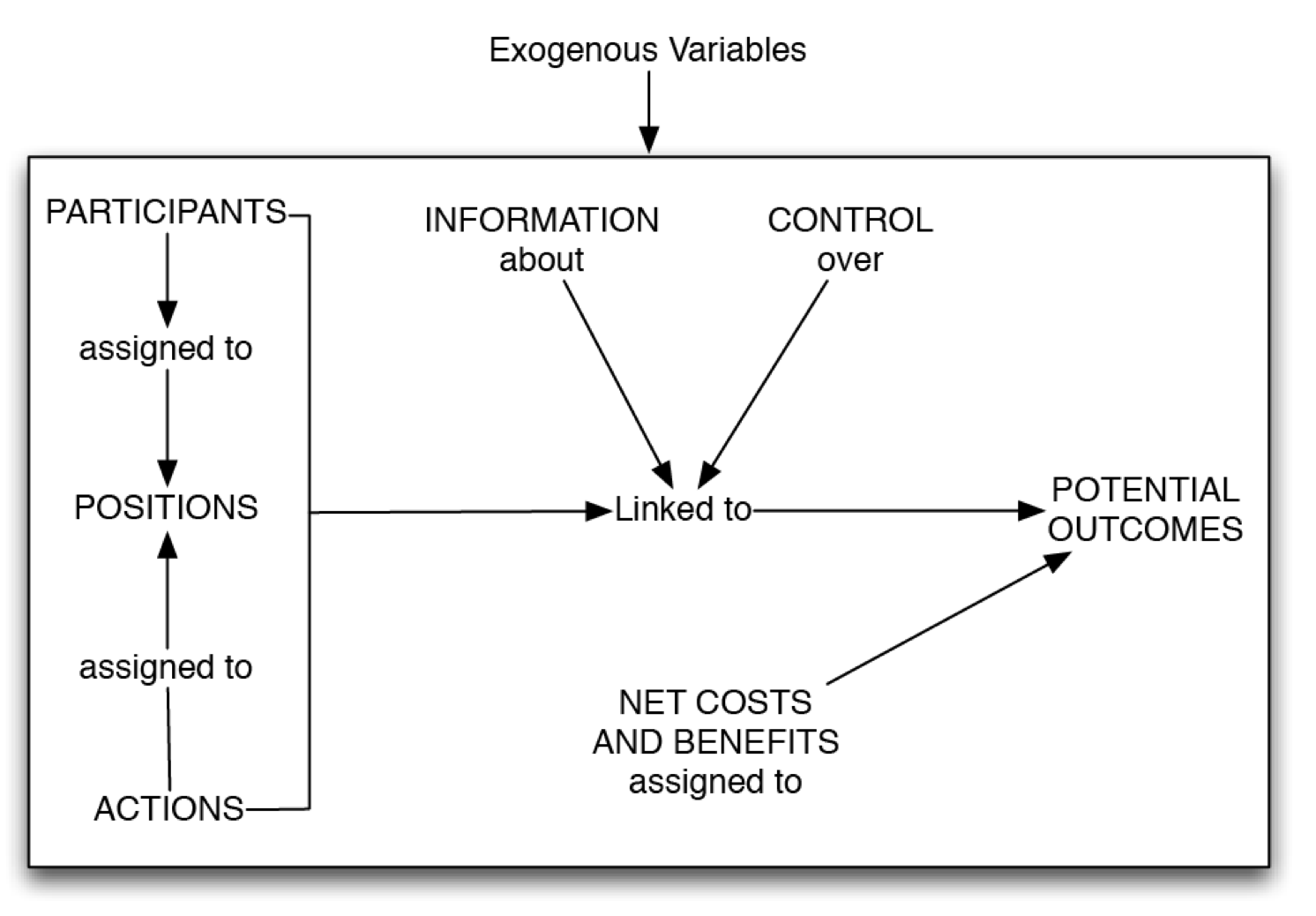

When people interact in situations that involve institutions they can make choices whether or not to follow these. The choice depends on many things, such as the perceived legitimacy of the institutions, the people involved in sustaining (or creating) it and the conformity among people affected by it. In institutional analysis one often rephrases this in terms of a game that is played repeatedly between participants. The cost/benefits of the different choices depend on personal preferences, knowledge and experience, as well as anticipated responses of other participants. Thus, the action arena is a complex adaptive system itself and institutions can evolve over time in both form and efficiency based on the choices made by all the participants

An important part of institutions is to structure society. In most countries today, we have constitutions (i.e. institutions) that determine how everyone in the society can participate in selecting temporary leader (a position) and how accountability of these leaders is handled. With positions come associated actions, such as legislation or enforcement. In smaller communities these can be informal, e.g. when people rise to the task of leading others.

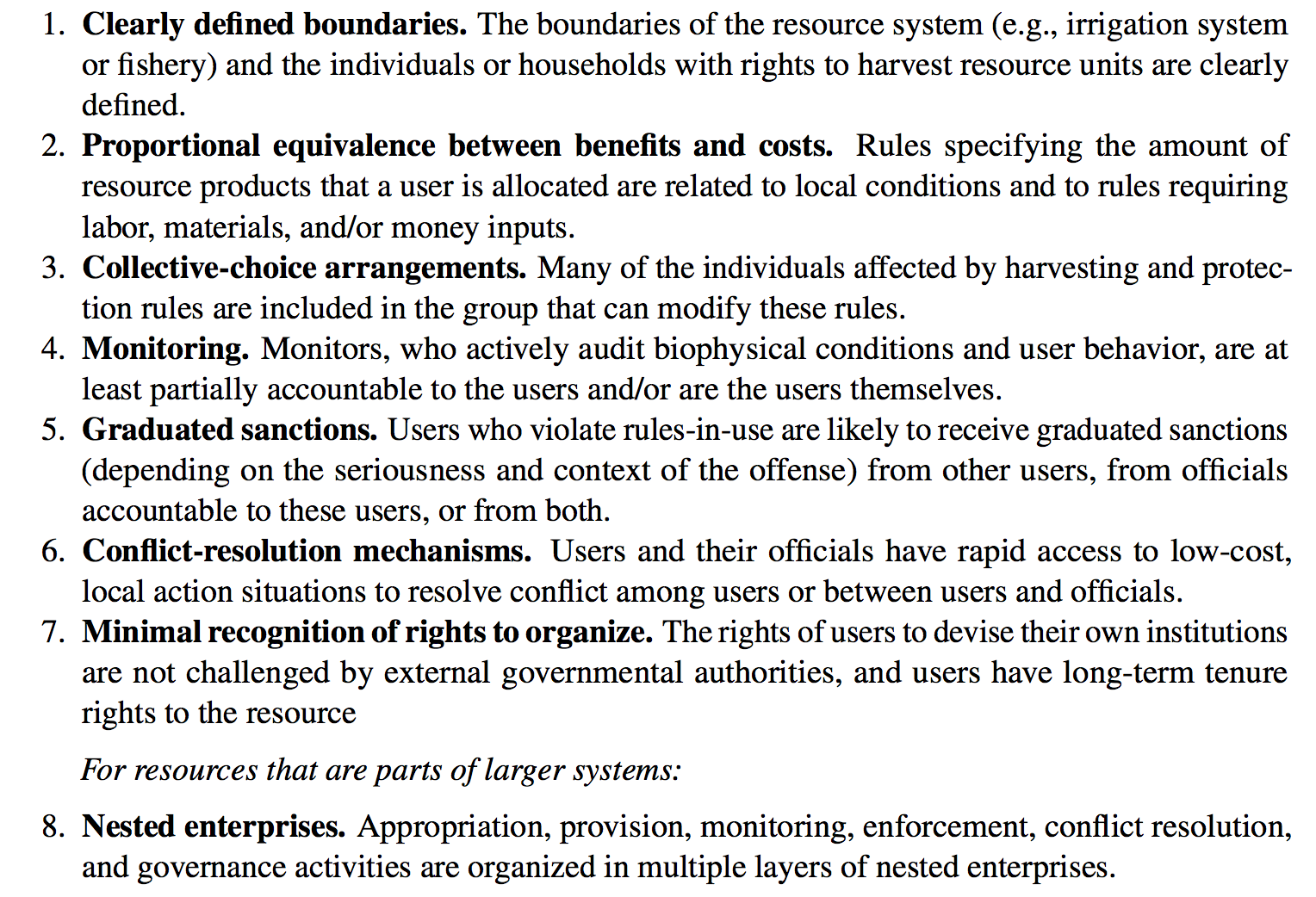

Rules for managing the tragedy of the commons

The holy grail of sustainability science has been the problem of the tragedy of the commons. How can we sustainably use a shared resource without strong laws or privatization? Elinor Ostrom and her co-workers have from an analysis of many successful and unsuccessful case studies come up with a list of eight design principles for governance that increase the chance of success based on careful analysis of institutions from successful cases:

Further reading

Your one-stop-document for reading up on institutional dynamics can be found in the wonderful text book by John M. Anderies and Marco Janssen a tribute to Elinor Ostrom provided for free!

Contributors

Jon Norberg

Leave a Comment